- Home

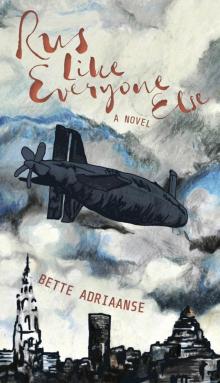

- Bette Adriaanse

Rus Like Everyone Else

Rus Like Everyone Else Read online

The Unnamed Press

1551 Colorado Blvd., Suite #201

Los Angeles, CA 90041

www.unnamedpress.com

Published in North America by The Unnamed Press.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Copyright 2015 © Bette Adriaanse

ISBN: 978-1-939419-59-0

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015952489

This book is distributed by Publishers Group West

Designed by Jaya Nicely

Cover design by Scott Arany

Cover art by Bette Adriaanse

A portion of this novel was originally published in Structo Magazine in 2012

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are wholly fictional or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. Permissions inquiries may be directed to [email protected].

Contents

Night

About the Author

NIGHT

There you are.

It’s night now, and if you are coming to see me you need to take the night bus, number seven in an easterly direction. The city is dark and you’ll see the yellow lights of the streetlamps flash by behind your own reflection in the bus window.

“Canal Street,” the driver announces in a tired voice. That’s where you get off. The bus stop is on the bridge between the old part of the neighborhood, with the low flats and the three-story houses, and the new part, with the glass apartment buildings and the construction sites. You see the boats rocking in the black water of the canal; the windows of the flats across the water are dark. It is late, but if you turn around toward that tall glass apartment building behind you, and look up to the seventh floor, you’ll see one window that is lit by a desk light. Behind that window sits a girl with a blond ponytail, looking back at you. That is me.

Down below, next to the front door, there is a list of all the people who live in my building. You press the buzzer that says LUCY and my voice says, “Of course, I’m always here for you,” through the machine. You come into my room and hang your coat over the chair, and I am sitting here by the window as I always am.

“Come stand next to me,” I say. Then I point out the window.

You see those flats and those houses across the water? I know everyone who lives there. I know every name and I know a lot of things about them too. In my profession you get to know a lot very quickly; it is like I have been standing in a corner of their living room, so to speak. That is how I watch over them.

There, in that low dark flat right across from us, the light blue curtains on the fourth floor, that’s where Mrs. Blue lives. I call her Grandma in my mind sometimes. She is not my real grandma, of course, but she does look like one a lot. Her round, wrinkled face lies like a multicolored raisin on the pillow. She always wears blue eye shadow and wrinkled pink lipstick to bed. She is almost deaf; the white noise in the blue-colored bedroom comes from a radio she does not hear. That radio has been on for almost a year now, just as long as Mr. Blue has been gone. He did not switch it off when he left.

One apartment to the right from Mrs. Blue’s, behind those white curtains, lives the girl with the black hair called the secretary. At this moment, she is having the same dream she always has, the dream in which she is waiting for something. The clock you hear ticking so loudly is in the living room. Although she’s been here for almost a year now, she still hasn’t unpacked any of her boxes. Her things fill only one-tenth of the room.

Next to Mrs. Blue and the secretary’s building is a side street called Low Street. Do you see those old houses right at the beginning of that street? Squint your eyes and you’ll see one fourth-floor apartment on the corner. On this floor lives a young man who has no surname. His only name is Rus, after his father, a Russian sailor he’s never met. Rus too is sleeping; his short dark hair contrasts with his flowery sheets. There is something about Rus—maybe it is the way he lies like a child on his belly, or maybe it’s the soft features under his two-day beard—that makes him look like he’s not fit for this world.

In a few hours, you’ll see the sun come up over Halfords auto-center. One by one the people in my neighborhood will wake up again. Alarm clocks will start ringing in the flats and the houses, people will walk dozily to their bathrooms, curtains open. Mrs. Blue will appear in her window over there—she always combs her hair by the window at seven o’clock. And I’ll get ready too. I’ll put on my Royal Mail trousers, my Royal Mail coat, and pull my ponytail through my Royal Mail cap. You’ll stay here, by the window, and you’ll see me cycle down below along the canal, toward the Royal Mail Centre in the business district. There, I sort the envelopes while my boss counts the days till his retirement out loud. At ten, my round starts. Like every morning I bring the letters and the bills and the warnings and the postcards, shouting “hiya” and “good morning” left and right, waking up the lazy with my mailbox clatter.

RUS

Flap.

Rus was lying in his tracksuit bottoms under his flowery duvet in his bed when he heard that sound for the first time. It had been an ordinary Thursday morning until this sound had rung out in his apartment, flapped, and disappeared again.

“I heard something,” Rus said to himself under the duvet. “It was a short sound. Short, but very clear.” He didn’t move. “I don’t know if I have ever heard that sound before.” He listened with deep concentration for a while, but his apartment was quiet again.

“This is unusual.” He waited for a bit. “I really should get out of bed and take a look.”

Rus opened his eyes and looked around the blackness under the duvet. He had just reached an extreme level of comfort under the covers and he had spent a lot of time working toward it, patiently shifting and turning on the mattress. “Therefore,” Rus mumbled, “therefore, it would be wiser to calmly consider whether I truly never have heard that sound before, instead of jumping out of the bed like some kind of police detective.”

One by one, Rus went over the sounds he could hear in his apartment. There was the sound of the rain, which sounded like ritititi on his tin roof; there were the sounds of the trams in the main street that squeaked and squealed when they braked. There was always some siren sounding somewhere in the distance, sometimes coming closer and sometimes fading away.

Then there was the tick and the tack his wooden doors made, a drip from the tap, and caaaw from the gull that nested in his drainpipe, under the roof. Occasionally, there was a massive clangbangbang when someone dropped their trash from the balcony, and of course there was the sound of the refrigerator, which sometimes said tr. His neighbor on the ground floor had an alarm that he set off every Monday to test it; some lonely drunkard strolled down Low Street now and then shouting “Everything-is-going-to-hell-I-tell-you”; and there was a continuous swoosh in the background from the cars. And last but not least there was dingdong, a sound Rus had heard just last winter when his doorbell had rung.

No, Rus concluded, there were many sounds in his apartment, but flap wasn’t one of them, flap was a stranger, and when Rus pulled the duvet from his head his suspicion that no good would come from this sound was confirmed. In the middle of the dark floor of his apartment a bright white envelope had appeared. Slowly, Rus got up from the bed, put on a T-shirt, and walked toward the stainless white envelope that had intruded on his apartment.

RUS AND THE LETTER

It took Rus a long time to find the post office, since he had never been there before, and it turned out to be the large orange building next to the supermarket. It had a square hallwa

y, and the post office employees sat behind windows on the opposite side of the entrance. Rus waited for a very long time until it turned out he had to get a number from a pole and then he got it and then he waited a very long time again. But now it was his turn. The woman behind the window had broad shoulders and red hair.

“First of all,” Rus said, “I’d like to return this.” Rus held the letter in front of the window. Then he shoved it in the slot under the window toward the lady. “Secondly,” he continued, “I wish to declare that I don’t need any more mail, ever. Please inform the postman.”

The woman behind the window lifted her eyebrows and smiled at Rus. After that, she took the letter, turned it around, and shoved it back to Rus’s side of the window.

“You’re giving it back,” Rus said.

“Yes,” the woman said.

Rus looked at the letter. He put his hands on the paper and tried to push it back in the slot, but the woman blocked it with her hands. “I need the letter to go behind the window,” Rus said.

“You mean in front of the window,” the woman said.

“I am in front of the window,” Rus said, “and I want the letter to go behind the window, so that the window is between the letter and me. If you could move your hands, please.”

“You are behind the window,” the woman said. “I watched you fuss around with your tax bill behind the window like watching television.”

“It is not my tax bill,” Rus said. “I never get bills!”

The woman brought her face close to the little holes in the window. “When I am at home, I watch the people behind my window, walking and driving down the street. One day I saw an old lady fall into the bushes. It took fifteen minutes until someone helped her out of there. Nobody cares anymore, nowadays.”

“Madam,” Rus said, bringing his face close to the window too. “I just want to return this letter. I don’t want it. It makes me feel nervous and unpleasant. And all I’m asking of you is to take it back and tell the postman I don’t need his services. Would you do that?”

The woman smiled at Rus. She smiled for a while without saying anything, as if there weren’t a lot of people waiting with numbers. “Sir,” the woman said eventually, “the post is not sent by the post. It is sent by the sender.”

“Ah,” Rus said. “I see. I apologize. In that case, please inform the sender that I don’t want it anymore.” He paused to think. “All the senders.”

“It’s not possible,” the woman said.

“If you knew what kind of things they say in this letter,” Rus replied. “One moment I was in my bed, not harming anyone, and the next moment I am bombarded with demands for this and for that and for money that I do not have!” He was aware that he was yelling but he couldn’t stop. “They threaten me in that letter! They say two thousand six hundred fifteen immediately because otherwise they will be forced to regretfully sell my bed and my kitchen and my clothes, and I don’t want that! I need my bed and my kitchen! And my clothes!”

“Debt”—the woman nodded—“most of our letters are about debt. You are funny to watch. When you get upset you get red spots on your neck and you twist your face while you speak. But my lunch break starts now.”

The woman shoved her chair back and switched off the lights behind her window. “Returning letters won’t help you,” she said. “The letters are merely the way it manifests itself. I would read that letter very carefully and pay up. If you ignore it, something huge will be set in motion.”

“What do you mean? What is that thing that is set in motion? How do I see it coming?” Rus asked, but the woman did not reply. She reached for her purse and rolled down the curtain, leaving Rus standing there, alone in the post office among the waiting people, who did not look at him but at the screen that said the numbers.

MRS. BLUE

The red colors from the television poured into Mrs. Blue’s living room, painting her blue walls pink. She was sitting close to the television, the sound turned up loud.

Grace was standing in front of a large wooden dresser, wearing a wedding dress. “I do want to marry you, Rick,” she said to a picture she kept in her locket. “But I need to know what you’re keeping from me.”

“My god, Grace,” Mrs. Blue exclaimed, “just open the dresser!”

“Forgive me, Rick,” Grace whispered.

“Rick is an asshole,” Mrs. Blue said. “Go on.”

Slowly, Grace closed the locket. She glanced over her shoulder, took a hairpin out of her hair and stuck it in the lock of the dresser.

Mrs. Blue squeezed the armrest of the couch. She ignored her doorbell ringing in the hallway and turned up the sound of the television.

On the television the doorknob to the hallway slowly turned around. Rick came up behind Grace, holding a baseball bat behind his back. Grace’s eyes widened wide with terror when she saw his reflection appear behind her in the mirror. Her face became large on the screen. Then the commercials started playing.

Mrs. Blue exhaled and fell back on the couch cushions. “I warned you,” she said, pointing at the television. “I told you not to get involved with him.” She got up from the sofa leaning on her cane and walked to the kitchen, still ignoring the doorbell. “You gotta let them make their own mistakes, they say,” Mrs. Blue said to herself as she poured hot water in the teapot. “But I don’t know if I can let her go on like this.” She dropped the tea bag in the water and looked into the pot as she pulled it up and down. “People are going to get hurt this way.”

In the hallway the doorbell sounded again. Someone was pressing her doorbell button long and uninterruptedly. With the teapot in her left hand and the cane in her right, Mrs. Blue shuffled back into the living room where Grace’s tune was already playing again.

“The heart is a restless thing,” the deep voice-over sang, “where will it take us next? Welcome back to Change of Hearts.”

Mrs. Blue swayed from side to side on the couch, softly singing her own words to the theme tune as she waited for Gracie.

THE SECRETARY

The secretary walked into the hallway of her apartment. She hung up her coat and looked through the mail. It was all for Mrs. Blue, mostly funeral advertisements, which she put in the bin, and one postcard, which she kept. She’d been getting Mrs. Blue’s mail for a while now; the post girl always put it in her postbox when Mrs. Blue’s was full.

The secretary put down her bag and the card on the kitchen table. She wondered why Mrs. Blue never answered her door anymore and didn’t pick up the phone. She did see her walking down the street sometimes, pushing her rolling walker to the supermarket, so there was no justification yet to use the emergency key she’d asked for from Mrs. Blue when she’d moved in.

The secretary sat down on the chair by the table. Rain was streaming down the kitchen window. She took her diary out of her purse and browsed through the empty pages. “I see,” she said, although there was nothing to see. The ticking of the clock echoed in the apartment. “Well, well,” the secretary continued for no reason. “All right then.”

She got up from the table and looked out the window. The post girl was cycling past the canal, trying to put her raincoat on while pedaling. The secretary took the postcard from the table. It had a map of a city on it and “Greetings from New York.”

“Dear Ma,” it read on the other side. “How are you? I am sorry I could not make it for your birthday. Busy, busy, you know how it is. Please write me back, Ma. Everyone sends you their best. Glenn.”

Glenn was Mrs. Blue’s son. She had seen his picture in her apartment. He was bald, Glenn, but his face looked friendly. There was a return envelope attached to the card with Glenn’s address on it and a stamp. The secretary held it up in the air. The sun shone on the paper. It wasn’t raining anymore. She filled a glass with water, drank it, washed and dried the glass and placed it back in the cupboard. Then she returned to the table and crossed out “Ma” in the postcard.

“‘Dear Laura,’” she read out loud. “‘Ho

w are you? I am sorry I could not make it for your birthday. Busy, busy, you know how it is. Please write me back, Laura. Everyone sends you their best.’” She repeated the sentence “please write me back, Laura” a few times. It had been a long time since she heard someone say her name. The last one had been the manager, during her job interview.

“Laura Zimmerman can come in,” he said in a bored voice, the same voice her doctor used when he called her from the waiting room. She’d written her name on a contract that day, a contract that said, “Laura Zimmerman, hereon referred to as the secretary.”

She remembered the manager taking the contract, putting it in a drawer and locking it. Since then, he called her “secretary.” Or “my dearest secretary,” when he needed his dry cleaning picked up. The secretary thought about her name, lying locked away in that drawer. It was as though it had been taken out of the air that day.

“Which is a good thing,” she reassured herself, “a necessary thing. This will lead to things, soon things will start, like they start for everybody.” She paused for a little bit. Any moment now, she thought, any moment now.

She wanted to continue thinking about those things that would start any moment now, but she wasn’t really sure anymore what she meant. There was a silence in her head and she sat quietly, looking at the unpacked boxes and the white walls. Then she took the sheet of paper from her diary and wrote “Dear Glenn. Thank you for your beautiful card. The birthday was wonderful. All is well—I have a job as a secretary and a spacious apartment. How are you?”

THE TAX BILL

Rus was pacing down the street from the post office to his house, his gaze fixed on the letter from the tax office, nervously repeating specific words or sentences that upset him.

“Dear Mr. Rus. Recently, the existence of your ‘accommodation’ at Low Street 1 came to our attention. The construction of this ‘apartment’ was never reported to the Department of Planning and Building, and it is not mentioned anywhere in the City Plans of ’85 or ’08 (see Book 2. Appendix 5. City Plans).”

Rus Like Everyone Else

Rus Like Everyone Else